Ruby Hacking Guide

Translated by Robert GRAVINA & ocha-

Chapter 10: Parser

Outline of this chapter

Parser construction

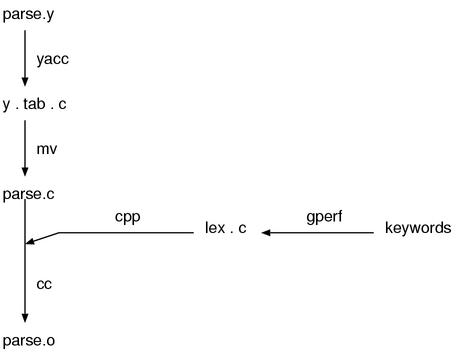

The main source of the parser is parser.y.

Because it is *.y, it is the input for yacc

and parse.c is generated from it.

Although one would expect lex.c to contain the scanner, this is not the case.

This file is created by gperf, taking the file keywords as input, and

defines the reserved word hashtable. This tool-generated lex.c is #included

in (the also tool-generated) parse.c. The details of this process is somewhat

difficult to explain at this time, so we shall return to this later.

Figure 1 shows the parser construction process. For the benefit of those readers

using Windows who may not be aware, the mv (move) command creates a new copy

of a file and removes the original. cc is, of course, the C compiler and cpp

the C pre-processor.

Dissecting parse.y

Let’s now look at parse.y in a bit more detail. The following figure presents

a rough outline of the contents of parse.y.

▼ parse.y

%{

header

%}

%union ....

%token ....

%type ....

%%

rules

%%

user code section

parser interface

scanner (character stream processing)

syntax tree construction

semantic analysis

local variable management

ID implementation

As for the rules and definitions part, it is as previously described. Since this part is indeed the heart of the parser, I’ll start to explain it ahead of the other parts in the next section.

There are a considerable number of support functions defined in the user code section, but roughly speaking, they can be divided into the six parts written above. The following table shows where each of parts are explained in this book.

| _. Part | _. Chapter | _. Section |

| Parser interface | This chapter | Section 3 “Scanning” |

| Scanner | This chapter | Section 3 “Scanning” |

| Syntax tree construction | Chapter 12 “Syntax tree construction” | Section 2 “Syntax tree construction” |

| Semantic analysis | Chapter 12 “Syntax tree construction” | Section 3 “Semantic analysis” |

| Local variable management | Chapter 12 “Syntax tree construction” | Section 4 “Local variables” |

ID implementation |

Chapter 3 “Names and name tables” | Section 2 “ID and symbols” |

General remarks about grammar rules

Coding rules

The grammar of ruby conforms to a coding standard and is thus easy to read

once you are familiar with it.

Firstly, regarding symbol names, all non-terminal symbols are written in lower

case characters. Terminal symbols are prefixed by some lower case character and

then followed by upper case. Reserved words (keywords) are prefixed with the

character k. Other terminal symbols are prefixed with the character t.

▼ Symbol name examples

| _. Token | _. Symbol name |

| (non-terminal symbol) | bodystmt |

if |

kIF |

def |

kDEF |

rescue |

kRESCUE |

varname |

tIDENTIFIER |

ConstName |

tCONST |

| 1 | tINTEGER |

The only exceptions to these rules are klBEGIN and klEND. These symbol names

refer to the reserved words for “BEGIN” and “END”, respectively, and the l

here stands for large. Since the reserved words begin and end already

exist (naturally, with symbol names kBEGIN and kEND), these non-standard

symbol names were required.

Important symbols

parse.y contains both grammar rules and actions, however, for now I would like

to concentrate on the grammar rules alone. The script sample/exyacc.rb can be

used to extract the grammar rules from this file.

Aside from this, running yacc -v will create a logfile y.output

which also contains the grammar rules,

however it is rather difficult to read. In this chapter I have used a slighty

modified version of exyacc.rb\footnote{modified exyacc.rb:tools/exyacc2.rb

located on the attached CD-ROM} to extract the grammar rules.

▼ parse.y(rules)

program : compstmt

bodystmt : compstmt

opt_rescue

opt_else

opt_ensure

compstmt : stmts opt_terms

:

:

The output is quite long - over 450 lines of grammar rules - and as such I have only included the most important parts in this chapter.

Which symbols, then, are the most important? The names such as program, expr,

stmt, primary, arg etc. are always very important. It’s because they

represent the general parts of the grammatical elements of a programming

language. The following table outlines the elements we should generally focus on

in the syntax of a program.

| _. Syntax element | _. Predicted symbol names |

| Program | program prog file input stmts whole |

| Sentence | statement stmt |

| Expression | expression expr exp |

| Smallest element | primary prim |

| Left hand side of an expression | lhs(left hand side) |

| Right hand side of an expression | rhs(right hand side) |

| Function call | funcall function_call call function |

| Method call | method method_call call |

| Argument | argument arg |

| Function definition | defun definition function fndef |

| Declarations | declaration decl |

In general, programming languages tend to have the following hierarchy structure.

| _. Program element | _. Properties |

| Program | Usually a list of statements |

| Statement | What can not be combined with the others. A syntax tree trunk. |

| Expression | What is a combination by itself and can also be a part of another |

| expression. A syntax tree internal node. | |

| Primary | An element which can not be further decomposed. A syntax tree leaf node. |

The statements are things like function definitions in C or class definitions

in Java. An expression can be a procedure call, an arithmetic expression

etc., while a primary usually refers to a string literal or number. Some languages

do not contain all of these symbol types, however they generally contain some

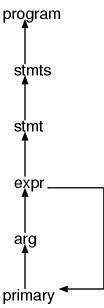

kind of hierarchy of symbols such as program→stmt→expr→primary.

However, a structure at a low level can be contained by a superior structure. For example, in C a function call is an expression but it can solely be put. It means it is an expression but it can also be a statement.

Conversely, when surrounded in parentheses, expressions become primaries. It is because the lower the level of an element the higher the precedence it has.

The range of statements differ considerably between programming languages. Let’s consider assignment as an example. In C, because it is part of expressions, we can use the value of the whole assignment expression. But in Pascal, assignment is a statement, we cannot do such thing. Also, function and class definitions are typically statements however in languages such as Lisp and Scheme, since everything is an expression, they do not have statements in the first place. Ruby is close to Lisp’s design in this regard.

Program structure

Now let’s turn our attention to the grammar rules of ruby. Firstly,

in yacc, the left hand side of the first rule represents the entire grammar.

Currently, it is program.

Following further and further from here,

as the same as the established tactic,

the four program stmt expr primary will be found.

With adding arg to them, let’s look at their rules.

▼ ruby grammar (outline)

program : compstmt

compstmt : stmts opt_terms

stmts : none

| stmt

| stmts terms stmt

stmt : kALIAS fitem fitem

| kALIAS tGVAR tGVAR

:

:

| expr

expr : kRETURN call_args

| kBREAK call_args

:

:

| '!' command_call

| arg

arg : lhs '=' arg

| var_lhs tOP_ASGN arg

| primary_value '[' aref_args ']' tOP_ASGN arg

:

:

| arg '?' arg ':' arg

| primary

primary : literal

| strings

:

:

| tLPAREN_ARG expr ')'

| tLPAREN compstmt ')'

:

:

| kREDO

| kRETRY

If we focus on the last rule of each element,

we can clearly make out a hierarchy of program→stmt→expr→arg→

primary.

Also, we’d like to focus on this rule of primary.

primary : literal

:

:

| tLPAREN_ARG expr ')' /* here */

The name tLPAREN_ARG comes from t for terminal symbol, L for left and

PAREN for parentheses - it is the open parenthesis. Why this isn’t '('

is covered in the next section “Context-dependent scanner”. Anyway, the purpose

of this rule is demote an expr to a primary. This creates

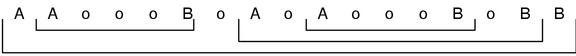

a cycle which can be seen in Figure 2, and the arrow shows how this rule is

reduced during parsing.

expr demotionThe next rule is also particularly interesting.

primary : literal

:

:

| tLPAREN compstmt ')' /* here */

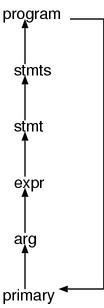

A compstmt, which equals to the entire program (program), can be demoted to

a primary with this rule. The next figure illustrates this rule in action.

program demotionThis means that for any syntax element in Ruby, if we surround it with

parenthesis it will become a primary and can be passed as an argument to a

function, be used as the right hand side of an expression etc.

This is an incredible fact.

Let’s actually confirm it.

p((class C; end))

p((def a() end))

p((alias ali gets))

p((if true then nil else nil end))

p((1 + 1 * 1 ** 1 - 1 / 1 ^ 1))

If we invoke ruby with the -c option (syntax check), we get the following

output.

% ruby -c primprog.rb

Syntax OK

Indeed, it’s hard to believe but, it could actually pass. Apparently, we did not get the wrong idea.

If we care about the details,

since there are what rejected by the semantic analysis (see also Chapter 12

“Syntax tree construction”), it is not perfectly possible.

For example passing a return statement as an argument to a

function will result in an error.

But at least at the level of the outlooks, the “surrounding

anything in parenthesis means it can be passed as an argument to a function”

rule does hold.

In the next section I will cover the contents of the important elements one by one.

program

▼ program

program : compstmt

compstmt : stmts opt_terms

stmts : none

| stmt

| stmts terms stmt

As mentioned earlier,

program represents the entire grammar that means the entire program.

That program equals to compstmts,

and compstmts is almost equivalent to stmts.

That stmts is a list of stmts delimited by terms.

Hence, the entire program is a list of stmts delimited by terms.

terms is (of course) an abbreviation for “terminators”, the symbols that

terminate the sentences, such as semicolons or newlines.

opt_terms means “OPTional terms”. The definitions are as follows:

▼ opt_terms

opt_terms :

| terms

terms : term

| terms ';'

term : ';'

| '\n'

The initial ; or \n of a terms can be followed by any number of ; only; based on that, you might start thinking that if there are 2 or more consecutive newlines, it could cause a problem. Let’s try and see what actually happens.

1 + 1 # first newline

# second newline

# third newline

1 + 1

Run that with ruby -c.

% ruby -c optterms.rb

Syntax OK

Strange, it worked! What actually happens is this: consecutive newlines are simply discarded by the scanner, which returns only the first newline in a series.

By the way, although we said that program is the same as compstmt, if that was really true, you would question why compstmt exists at all. Actually, the distinction is there only for execution of semantic actions. program exists to execute any semantic actions which should be done once in the processing of an entire program. If it was only a question of parsing, program could be omitted with no problems at all.

To generalize this point, the grammar rules can be divided into 2 groups: those which are needed for parsing the program structure, and those which are needed for execution of semantic actions. The none rule which was mentioned earlier when talking about stmts is another one which exists for executing actions – it’s used to return a NULL pointer for an empty list of type NODE*.

stmt

Next is stmt. This one is rather involved, so we’ll look into it a bit at a time.

▼ stmt(1)

stmt : kALIAS fitem fitem

| kALIAS tGVAR tGVAR

| kALIAS tGVAR tBACK_REF

| kALIAS tGVAR tNTH_REF

| kUNDEF undef_list

| stmt kIF_MOD expr_value

| stmt kUNLESS_MOD expr_value

| stmt kWHILE_MOD expr_value

| stmt kUNTIL_MOD expr_value

| stmt kRESCUE_MOD stmt

| klBEGIN '{' compstmt '}'

| klEND '{' compstmt '}'

Looking at that, somehow things start to make sense. The first few have alias, then undef, then the next few are all something followed by _MOD – those should be statements with postposition modifiers, as you can imagine.

expr_value and primary_value are grammar rules which exist to execute semantic actions. For example, expr_value represents an expr which has a value. Expressions which don’t have values are return and break, or return/break followed by a postposition modifier, such as an if clause. For a detailed definition of what it means to “have a value”, see chapter 12, “Syntax Tree Construction”. In the same way, primary_value is a primary which has a value.

As explained earlier, klBEGIN and klEND represent BEGIN and END.

▼ stmt(2)

| lhs '=' command_call

| mlhs '=' command_call

| var_lhs tOP_ASGN command_call

| primary_value '[' aref_args ']' tOP_ASGN command_call

| primary_value '.' tIDENTIFIER tOP_ASGN command_call

| primary_value '.' tCONSTANT tOP_ASGN command_call

| primary_value tCOLON2 tIDENTIFIER tOP_ASGN command_call

| backref tOP_ASGN command_call

Looking at these rules all at once is the right approach.

The common point is that they all have command_call on the right-hand side. command_call represents a method call with the parentheses omitted. The new symbols which are introduced here are explained in the following table. I hope you’ll refer to the table as you check over each grammar rule.

lhs |

the left hand side of an assignment (Left Hand Side) |

mlhs |

the left hand side of a multiple assignment (Multiple Left Hand Side) |

var_lhs |

the left hand side of an assignment to a kind of variable (VARiable Left Hand Side) |

tOP_ASGN |

compound assignment operator like += or *= (OPerator ASsiGN) |

aref_args |

argument to a [] method call (Array REFerence) |

tIDENTIFIER |

identifier which can be used as a local variable |

tCONSTANT |

constant identifier (with leading uppercase letter) |

tCOLON2 |

:: |

backref |

$1 $2 $3... |

aref is a Lisp jargon.

There’s also aset as the other side of a pair,

which is an abbreviation of “array set”.

This abbreviation is used at a lot of places in the source code of ruby.

▼ `stmt` (3)

| lhs '=' mrhs_basic

| mlhs '=' mrhs

These two are multiple assignments.

mrhs has the same structure as mlhs and it means multiple rhs (the right hand side).

We’ve come to recognize that knowing the meanings of names makes the comprehension much easier.

▼ `stmt` (4)

| expr

Lastly, it joins to expr.

expr

▼ `expr`

expr : kRETURN call_args

| kBREAK call_args

| kNEXT call_args

| command_call

| expr kAND expr

| expr kOR expr

| kNOT expr

| '!' command_call

| arg

Expression. The expression of ruby is very small in grammar.

That’s because those ordinary contained in expr are mostly went into arg.

Conversely speaking, those who could not go to arg are left here.

And what are left are, again, method calls without parentheses.

call_args is an bare argument list,

command_call is, as previously mentioned, a method without parentheses.

If this kind of things was contained in the “small” unit,

it would cause conflicts tremendously.

However, these two below are of different kind.

expr kAND expr

expr kOR expr

kAND is “and”, and kOR is “or”.

Since these two have their roles as control structures,

they must be contained in the “big” syntax unit which is larger than command_call.

And since command_call is contained in expr,

at least they need to be expr to go well.

For example, the following usage is possible …

valid_items.include? arg or raise ArgumentError, 'invalid arg'

# valid_items.include?(arg) or raise(ArgumentError, 'invalid arg')

However, if the rule of kOR existed in arg instead of expr,

it would be joined as follows.

valid_items.include?((arg or raise)) ArgumentError, 'invalid arg'

Obviously, this would end up a parse error.

arg

▼ `arg`

arg : lhs '=' arg

| var_lhs tOP_ASGN arg

| primary_value '[' aref_args ']' tOP_ASGN arg

| primary_value '.' tIDENTIFIER tOP_ASGN arg

| primary_value '.' tCONSTANT tOP_ASGN arg

| primary_value tCOLON2 tIDENTIFIER tOP_ASGN arg

| backref tOP_ASGN arg

| arg tDOT2 arg

| arg tDOT3 arg

| arg '+' arg

| arg '-' arg

| arg '*' arg

| arg '/' arg

| arg '%' arg

| arg tPOW arg

| tUPLUS arg

| tUMINUS arg

| arg '|' arg

| arg '^' arg

| arg '&' arg

| arg tCMP arg

| arg '>' arg

| arg tGEQ arg

| arg '<' arg

| arg tLEQ arg

| arg tEQ arg

| arg tEQQ arg

| arg tNEQ arg

| arg tMATCH arg

| arg tNMATCH arg

| '!' arg

| '~' arg

| arg tLSHFT arg

| arg tRSHFT arg

| arg tANDOP arg

| arg tOROP arg

| kDEFINED opt_nl arg

| arg '?' arg ':' arg

| primary

Although there are many rules here, the complexity of the grammar is not

proportionate to the number of rules.

A grammar that merely has a lot of cases can be handled very easily by yacc,

rather, the depth or recursive of the rules has more influences the complexity.

Then, it makes us curious about the rules are defined recursively in the form

of arg OP arg at the place for operators,

but because for all of these operators their operator precedences are defined,

this is virtually only a mere enumeration.

Let’s cut the “mere enumeration” out from the arg rule by merging.

arg: lhs '=' arg /* 1 */

| primary T_opeq arg /* 2 */

| arg T_infix arg /* 3 */

| T_pre arg /* 4 */

| arg '?' arg ':' arg /* 5 */

| primary /* 6 */

There’s no meaning to distinguish terminal symbols from lists of terminal symbols,

they are all expressed with symbols with T_.

opeq is operator + equal,

T_pre represents the prepositional operators such as '!' and '~',

T_infix represents the infix operators such as '*' and '%'.

To avoid conflicts in this structure, things like written below become important (but, these does not cover all).

T_infixshould not contain'='.

Since args partially overlaps lhs,

if '=' is contained, the rule 1 and the rule 3 cannot be distinguished.

T_opeqandT_infixshould not have any common rule.

Since args contains primary,

if they have any common rule, the rule 2 and the rule 3 cannot be distinguished.

T_infixshould not contain'?'.

If it contains, the rule 3 and 5 would produce a shift/reduce conflict.

T_preshould not contain'?'or':'.

If it contains, the rule 4 and 5 would conflict in a very complicated way.

The conclusion is all requirements are met and this grammar does not conflict. We could say it’s a matter of course.

primary

Because primary has a lot of grammar rules, we’ll split them up and show them in parts.

▼ `primary` (1)

primary : literal

| strings

| xstring

| regexp

| words

| qwords

Literals.

literal is for Symbol literals (:sym) and numbers.

▼ `primary` (2)

| var_ref

| backref

| tFID

Variables.

var_ref is for local variables and instance variables and etc.

backref is for $1 $2 $3 …

tFID is for the identifiers with ! or ?, say, include? reject!.

There’s no possibility of tFID being a local variable,

even if it appears solely, it becomes a method call at the parser level.

▼ `primary` (3)

| kBEGIN

bodystmt

kEND

bodystmt contains rescue and ensure.

It means this is the begin of the exception control.

▼ `primary` (4)

| tLPAREN_ARG expr ')'

| tLPAREN compstmt ')'

This has already described. Syntax demoting.

▼ `primary` (5)

| primary_value tCOLON2 tCONSTANT

| tCOLON3 cname

Constant references. tCONSTANT is for constant names (capitalized identifiers).

Both tCOLON2 and tCOLON3 are ::,

but tCOLON3 represents only the :: which means the top level.

In other words, it is the :: of ::Const.

The :: of Net::SMTP is tCOLON2.

The reason why different symbols are used for the same token is to deal with the methods without parentheses. For example, it is to distinguish the next two from each other:

p Net::HTTP # p(Net::HTTP)

p Net ::HTTP # p(Net(::HTTP))

If there’s a space or a delimiter character such as an open parenthesis just before it,

it becomes tCOLON3. In the other cases, it becomes tCOLON2.

▼ `primary` (6)

| primary_value '[' aref_args ']'

Index-form calls, for instance, arr[i].

▼ `primary` (7)

| tLBRACK aref_args ']'

| tLBRACE assoc_list '}'

Array literals and Hash literals.

This tLBRACK represents also '[',

'[' means a '[' without a space in front of it.

The necessity of this differentiation is also a side effect of method calls

without parentheses.

The terminal symbols of this rule is very incomprehensible because they differs in just a character. The following table shows how to read each type of parentheses, so I’d like you to make use of it when reading.

▼ English names for each parentheses

| Symbol | English Name | | () | parentheses | | {} | braces | | [] | brackets |

▼ `primary` (8)

| kRETURN

| kYIELD '(' call_args ')'

| kYIELD '(' ')'

| kYIELD

| kDEFINED opt_nl '(' expr ')'

Syntaxes whose forms are similar to method calls.

Respectively, return, yield, defined?.

There arguments for yield, but return does not have any arguments. Why?

The fundamental reason is that yield itself has its return value but

return does not.

However, even if there’s not any arguments here,

it does not mean you cannot pass values, of course.

There was the following rule in expr.

kRETURN call_args

call_args is a bare argument list,

so it can deal with return 1 or return nil.

Things like return(1) are handled as return (1).

For this reason,

surrounding the multiple arguments of a return with parentheses

as in the following code should be impossible.

return(1, 2, 3) # interpreted as return (1,2,3) and results in parse error

You could understand more about around here if you will check this again after reading the next chapter “Finite-State Scanner”.

▼ `primary` (9)

| operation brace_block

| method_call

| method_call brace_block

Method calls. method_call is with arguments (also with parentheses),

operation is without both arguments and parentheses,

brace_block is either { ~ } or do ~ end

and if it is attached to a method, the method is an iterator.

For the question “Even though it is brace, why is do ~ end contained in

it?”, there’s a reason that is more abyssal than Marian Trench,

but again the only way to understand is reading

the next chapter “Finite-State Scanner”.

▼ `primary` (10)

| kIF expr_value then compstmt if_tail kEND # if

| kUNLESS expr_value then compstmt opt_else kEND # unless

| kWHILE expr_value do compstmt kEND # while

| kUNTIL expr_value do compstmt kEND # until

| kCASE expr_value opt_terms case_body kEND # case

| kCASE opt_terms case_body kEND # case(Form2)

| kFOR block_var kIN expr_value do compstmt kEND # for

The basic control structures.

A little unexpectedly, things appear to be this big are put inside primary,

which is “small”.

Because primary is also arg,

we can also do something like this.

p(if true then 'ok' end) # shows "ok"

I mentioned “almost all syntax elements are expressions”

was one of the traits of Ruby.

It is concretely expressed by the fact that if and while are in primary.

Why is there no problem if these “big” elements are contained in primary?

That’s because the Ruby’s syntax has a trait that “it begins with the terminal

symbol A and ends with the terminal symbol B”.

In the next section, we’ll think about this point again.

▼ `primary` (11)

| kCLASS cname superclass bodystmt kEND # class definition

| kCLASS tLSHFT expr term bodystmt kEND # singleton class definition

| kMODULE cname bodystmt kEND # module definition

| kDEF fname f_arglist bodystmt kEND # method definition

| kDEF singleton dot_or_colon fname f_arglist bodystmt kEND

# singleton method definition

Definition statements. I’ve called them the class statements and the class statements, but essentially I should have been called them the class primaries, probably. These are all fit the pattern “beginning with the terminal symbol A and ending with B”, even if such rules are increased a lot more, it would never be a problem.

▼ `primary` (12)

| kBREAK

| kNEXT

| kREDO

| kRETRY

Various jumps. These are, well, not important from the viewpoint of grammar.

Conflicting Lists

In the previous section, the question “is it all right that if is in such

primary?” was suggested.

To proof precisely is not easy,

but explaining instinctively is relatively easy.

Here, let’s simulate with a small rule defined as follows:

%token A B o

%%

element : A item_list B

item_list :

| item_list item

item : element

| o

element is the element that we are going to examine.

For example, if we think about if, it would be if.

element is a list that starts with the terminal symbol A and ends with B.

As for if, it starts with if and ends with end.

The o contents are methods or variable references or literals.

For an element of the list, the o or element is nesting.

With the parser based on this grammar, let’s try to parse the following input.

A A o o o B o A o A o o o B o B B

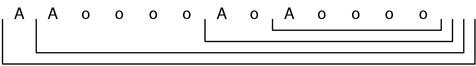

They are nesting too many times for humans to comprehend

without some helps such as indents.

But it becomes relatively easy if you think in the next way.

Because it’s certain that A and B which contain only several o between

them are going to appear, replace them to a single o when they appear.

All we have to do is repeating this procedure.

Figure 4 shows the consequence.

However, if the ending B is missing, …

%token A o

%%

element : A item_list /* B is deleted for an experiment */

item_list :

| item_list item

item : element

| o

I processed this with yacc and got 2 shift/reduce conflicts.

It means this grammar is ambiguous.

If we simply take B out from the previous one,

The input would be as follows.

A A o o o o A o A o o o o

This is hard to interpret in any way. However, there was a rule that “choose shift if it is a shift/reduce conflict”, let’s follow it as an experiment and parse the input with shift (meaning interior) which takes precedence. (Figure 5)

It could be parsed. However, this is completely different from the intention of the input, there becomes no way to split the list in the middle.

Actually, the methods without parentheses of Ruby is in the similar situation

to this. It’s not so easy to understand but

a pair of a method name and its first argument is A.

This is because, since there’s no comma only between the two,

it can be recognized as the start of a new list.

Also, the “practical” HTML contains this pattern.

It is, for instance, when </p> or </i> is omitted.

That’s why yacc could not be used for ordinary HTML at all.

Scanner

Parser Outline

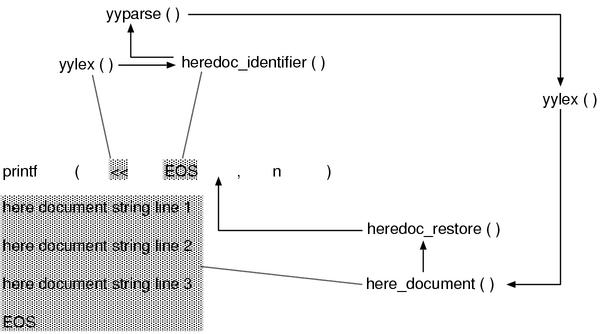

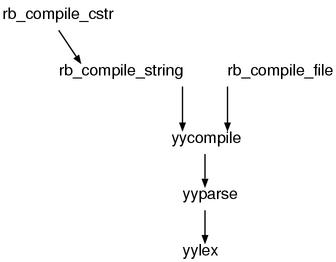

I’ll explain about the outline of the parser before moving on to the scanner. Take a look at Figure 6.

There are three official interfaces of the parser: rb_compile_cstr(),

rb_compile_string(), rb_compile_file().

They read a program from C string,

a Ruby string object and a Ruby IO object, respectively, and compile it.

These functions, directly or indirectly, call yycompile(),

and in the end, the control will be completely moved to yyparse(),

which is generated by yacc.

Since the heart of the parser is nothing but yyparse(),

it’s nice to understand by placing yyparse() at the center.

In other words, functions before moving on to yyparse() are all preparations,

and functions after yyparse() are merely chore functions being pushed around

by yyparse().

The rest functions in parse.y are auxiliary functions called by yylex(),

and these can also be clearly categorized.

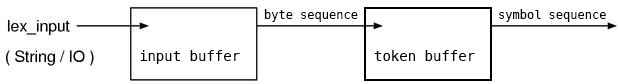

First, the input buffer is at the lowest level of the scanner.

ruby is designed so that you can input source programs via both Ruby IO

objects and strings.

The input buffer hides that and makes it look like a single byte stream.

The next level is the token buffer. It reads 1 byte at a time from the input buffer, and keeps them until it will form a token.

Therefore, the whole structure of yylex can be depicted as Figure 7.

The input buffer

Let’s start with the input buffer. Its interfaces are only the three: nextc(), pushback(), peek().

Although this is sort of insistent, I said the first thing is to investigate data structures. The variables used by the input buffer are the followings:

▼ the input buffer

2279 static char *lex_pbeg;

2280 static char *lex_p;

2281 static char *lex_pend;

(parse.y)

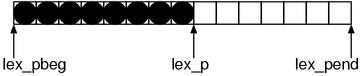

The beginning, the current position and the end of the buffer. Apparently, this buffer seems a simple single-line string buffer (Figure 8).

nextc()

Then, let’s look at the places using them.

First, I’ll start with nextc() that seems the most orthodox.

▼ `nextc()`

2468 static inline int

2469 nextc()

2470 {

2471 int c;

2472

2473 if (lex_p == lex_pend) {

2474 if (lex_input) {

2475 VALUE v = lex_getline();

2476

2477 if (NIL_P(v)) return -1;

2478 if (heredoc_end > 0) {

2479 ruby_sourceline = heredoc_end;

2480 heredoc_end = 0;

2481 }

2482 ruby_sourceline++;

2483 lex_pbeg = lex_p = RSTRING(v)->ptr;

2484 lex_pend = lex_p + RSTRING(v)->len;

2485 lex_lastline = v;

2486 }

2487 else {

2488 lex_lastline = 0;

2489 return -1;

2490 }

2491 }

2492 c = (unsigned char)*lex_p++;

2493 if (c == '\r' && lex_p <= lex_pend && *lex_p == '\n') {

2494 lex_p++;

2495 c = '\n';

2496 }

2497

2498 return c;

2499 }

(parse.y)

It seems that the first if is to test if it reaches the end of the input buffer.

And, the if inside of it seems, since the else returns -1 (EOF),

to test the end of the whole input.

Conversely speaking, when the input ends, lex_input becomes 0.

((errata: it does not. lex_input will never become 0 during ordinary scan.))

From this, we can see that strings are coming bit by bit into the input buffer.

Since the name of the function which updates the buffer is lex_getline,

it’s definite that each line comes in at a time.

Here is the summary:

if ( reached the end of the buffer )

if (still there's more input)

read the next line

else

return EOF

move the pointer forward

skip reading CR of CRLF

return c

Let’s also look at the function lex_getline(), which provides lines.

The variables used by this function are shown together in the following.

▼ `lex_getline()`

2276 static VALUE (*lex_gets)(); /* gets function */

2277 static VALUE lex_input; /* non-nil if File */

2420 static VALUE

2421 lex_getline()

2422 {

2423 VALUE line = (*lex_gets)(lex_input);

2424 if (ruby_debug_lines && !NIL_P(line)) {

2425 rb_ary_push(ruby_debug_lines, line);

2426 }

2427 return line;

2428 }

(parse.y)

Except for the first line, this is not important.

Apparently, lex_gets should be the pointer to the function to read a line,

lex_input should be the actual input.

I searched the place where setting lex_gets and this is what I found:

▼ set `lex_gets`

2430 NODE*

2431 rb_compile_string(f, s, line)

2432 const char *f;

2433 VALUE s;

2434 int line;

2435 {

2436 lex_gets = lex_get_str;

2437 lex_gets_ptr = 0;

2438 lex_input = s;

2454 NODE*

2455 rb_compile_file(f, file, start)

2456 const char *f;

2457 VALUE file;

2458 int start;

2459 {

2460 lex_gets = rb_io_gets;

2461 lex_input = file;

(parse.y)

rb_io_gets() is not an exclusive function for the parser

but one of the general-purpose library of Ruby.

It is the function to read a line from an IO object.

On the other hand, lex_get_str() is defined as follows:

▼ `lex_get_str()`

2398 static int lex_gets_ptr;

2400 static VALUE

2401 lex_get_str(s)

2402 VALUE s;

2403 {

2404 char *beg, *end, *pend;

2405

2406 beg = RSTRING(s)->ptr;

2407 if (lex_gets_ptr) {

2408 if (RSTRING(s)->len == lex_gets_ptr) return Qnil;

2409 beg += lex_gets_ptr;

2410 }

2411 pend = RSTRING(s)->ptr + RSTRING(s)->len;

2412 end = beg;

2413 while (end < pend) {

2414 if (*end++ == '\n') break;

2415 }

2416 lex_gets_ptr = end - RSTRING(s)->ptr;

2417 return rb_str_new(beg, end - beg);

2418 }

(parse.y)

lex_gets_ptr remembers the place it have already read.

This moves it to the next \n,

and simultaneously cut out at the place and return it.

Here, let’s go back to nextc.

As described, by preparing the two functions with the same interface,

it switch the function pointer when initializing the parser,

and the other part is used in common.

It can also be said that the difference of the code is converted to the data

and absorbed. There was also a similar method of st_table.

pushback()

With the knowledge of the physical structure of the buffer and nextc,

we can understand the rest easily.

pushback() writes back a character. If put it in C, it is ungetc().

▼ `pushback()`

2501 static void

2502 pushback(c)

2503 int c;

2504 {

2505 if (c == -1) return;

2506 lex_p--;

2507 }

(parse.y)

peek()

peek() checks the next character without moving the pointer forward.

▼ `peek()`

2509 #define peek(c) (lex_p != lex_pend && (c) == *lex_p)

(parse.y)

The Token Buffer

The token buffer is the buffer of the next level. It keeps the strings until a token will be able to cut out. There are the five interfaces as follows:

newtok |

begin a new token |

tokadd |

add a character to the buffer |

tokfix |

fix a token |

tok |

the pointer to the beginning of the buffered string |

toklen |

the length of the buffered string |

toklast |

the last byte of the buffered string |

Now, we’ll start with the data structures.

▼ The Token Buffer

2271 static char *tokenbuf = NULL;

2272 static int tokidx, toksiz = 0;

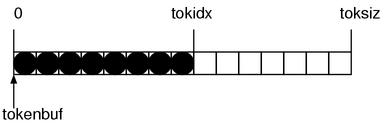

(parse.y)

tokenbuf is the buffer, tokidx is the end of the token

(since it is of int, it seems an index),

and toksiz is probably the buffer length.

This is also simply structured. If depicting it,

it would look like Figure 9.

Let’s continuously go to the interface and

read newtok(), which starts a new token.

▼ `newtok()`

2516 static char*

2517 newtok()

2518 {

2519 tokidx = 0;

2520 if (!tokenbuf) {

2521 toksiz = 60;

2522 tokenbuf = ALLOC_N(char, 60);

2523 }

2524 if (toksiz > 4096) {

2525 toksiz = 60;

2526 REALLOC_N(tokenbuf, char, 60);

2527 }

2528 return tokenbuf;

2529 }

(parse.y)

The initializing interface of the whole buffer does not exist,

it’s possible that the buffer is not initialized.

Therefore, the first if checks it and initializes it.

ALLOC_N() is the macro ruby defines and is almost the same as calloc.

The initial value of the allocating length is 60,

and if it becomes too big (> 4096),

it would be returned back to small.

Since a token becoming this long is unlikely,

this size is realistic.

Next, let’s look at the tokadd() to add a character to token buffer.

▼ `tokadd()`

2531 static void

2532 tokadd(c)

2533 char c;

2534 {

2535 tokenbuf[tokidx++] = c;

2536 if (tokidx >= toksiz) {

2537 toksiz *= 2;

2538 REALLOC_N(tokenbuf, char, toksiz);

2539 }

2540 }

(parse.y)

At the first line, a character is added.

Then, it checks the token length and if it seems about to exceed the buffer end,

it performs REALLOC_N().

REALLOC_N() is a realloc() which has the same way of specifying arguments

as calloc().

The rest interfaces are summarized below.

▼ `tokfix() tok() toklen() toklast()`

2511 #define tokfix() (tokenbuf[tokidx]='\0')

2512 #define tok() tokenbuf

2513 #define toklen() tokidx

2514 #define toklast() (tokidx>0?tokenbuf[tokidx-1]:0)

(parse.y)

There’s probably no question.

yylex()

yylex() is very long. Currently, there are more than 1000 lines.

The most of them is occupied by a huge switch statement,

it branches based on each character.

First, I’ll show the whole structure that some parts of it are left out.

▼ `yylex` outline

3106 static int

3107 yylex()

3108 {

3109 static ID last_id = 0;

3110 register int c;

3111 int space_seen = 0;

3112 int cmd_state;

3113

3114 if (lex_strterm) {

/* ... string scan ... */

3131 return token;

3132 }

3133 cmd_state = command_start;

3134 command_start = Qfalse;

3135 retry:

3136 switch (c = nextc()) {

3137 case '\0': /* NUL */

3138 case '\004': /* ^D */

3139 case '\032': /* ^Z */

3140 case -1: /* end of script. */

3141 return 0;

3142

3143 /* white spaces */

3144 case ' ': case '\t': case '\f': case '\r':

3145 case '\13': /* '\v' */

3146 space_seen++;

3147 goto retry;

3148

3149 case '#': /* it's a comment */

3150 while ((c = nextc()) != '\n') {

3151 if (c == -1)

3152 return 0;

3153 }

3154 /* fall through */

3155 case '\n':

/* ... omission ... */

case xxxx:

:

break;

:

/* branches a lot for each character */

:

:

4103 default:

4104 if (!is_identchar(c) || ISDIGIT(c)) {

4105 rb_compile_error("Invalid char `\\%03o' in expression", c);

4106 goto retry;

4107 }

4108

4109 newtok();

4110 break;

4111 }

/* ... deal with ordinary identifiers ... */

}

(parse.y)

As for the return value of yylex(),

zero means that the input has finished,

non-zero means a symbol.

Be careful that a extremely concise variable named “c” is used all over this function.

space_seen++ when reading a space will become helpful later.

All it has to do as the rest is to keep branching for each character and processing it, but since continuous monotonic procedure is lasting, it is boring for readers. Therefore, we’ll narrow them down to a few points. In this book not all characters will be explained, but it is easy if you will amplify the same pattern.

'!'

Let’s start with what is simple first.

▼ `yylex` - `'!'`

3205 case '!':

3206 lex_state = EXPR_BEG;

3207 if ((c = nextc()) == '=') {

3208 return tNEQ;

3209 }

3210 if (c == '~') {

3211 return tNMATCH;

3212 }

3213 pushback(c);

3214 return '!';

(parse.y)

I wrote out the meaning of the code, so I’d like you to read them by comparing each other.

case '!':

move to EXPR_BEG

if (the next character is '=' then) {

token is 「!=(tNEQ)」

}

if (the next character is '~' then) {

token is 「!~(tNMATCH)」

}

if it is neither, push the read character back

token is '!'

This case clause is short, but describes the important rule of the scanner.

It is “the longest match rule”.

The two characters "!=" can be interpreted in two ways: “! and =” or “!=”,

but in this case "!=" must be selected.

The longest match is essential for scanners of programming languages.

And, lex_state is the variable represents the state of the scanner.

This will be discussed too much

in the next chapter “Finite-State Scanner”,

you can ignore it for now.

EXPR_BEG indicates “it is clearly at the beginning”.

This is because

whichever it is ! of not or it is != or it is !~,

its next symbol is the beginning of an expression.

'<'

Next, we’ll try to look at '<' as an example of using yylval (the value of a symbol).

▼ `yylex`−`'>'`

3296 case '>':

3297 switch (lex_state) {

3298 case EXPR_FNAME: case EXPR_DOT:

3299 lex_state = EXPR_ARG; break;

3300 default:

3301 lex_state = EXPR_BEG; break;

3302 }

3303 if ((c = nextc()) == '=') {

3304 return tGEQ;

3305 }

3306 if (c == '>') {

3307 if ((c = nextc()) == '=') {

3308 yylval.id = tRSHFT;

3309 lex_state = EXPR_BEG;

3310 return tOP_ASGN;

3311 }

3312 pushback(c);

3313 return tRSHFT;

3314 }

3315 pushback(c);

3316 return '>';

(parse.y)

The places except for yylval can be ignored.

Concentrating only one point when reading a program is essential.

At this point, for the symbol tOP_ASGN of >>=, it set its value tRSHIFT.

Since the used union member is id, its type is ID.

tOP_ASGN is the symbol of self assignment,

it represents all of the things like += and -= and *=.

In order to distinguish them later,

it passes the type of the self assignment as a value.

The reason why the self assignments are bundled is, it makes the rule shorter. Bundling things that can be bundled at the scanner as much as possible makes the rule more concise. Then, why are the binary arithmetic operators not bundled? It is because they differs in their precedences.

':'

If scanning is completely independent from parsing, this talk would be simple.

But in reality, it is not that simple.

The Ruby grammar is particularly complex,

it has a somewhat different meaning when there’s a space in front of it,

the way to split tokens is changed depending on the situation around.

The code of ':' shown below is an example that a space changes the behavior.

▼ `yylex`−`':'`

3761 case ':':

3762 c = nextc();

3763 if (c == ':') {

3764 if (lex_state == EXPR_BEG || lex_state == EXPR_MID ||

3765 (IS_ARG() && space_seen)) {

3766 lex_state = EXPR_BEG;

3767 return tCOLON3;

3768 }

3769 lex_state = EXPR_DOT;

3770 return tCOLON2;

3771 }

3772 pushback(c);

3773 if (lex_state == EXPR_END ||

lex_state == EXPR_ENDARG ||

ISSPACE(c)) {

3774 lex_state = EXPR_BEG;

3775 return ':';

3776 }

3777 lex_state = EXPR_FNAME;

3778 return tSYMBEG;

(parse.y)

Again, ignoring things relating to lex_state,

I’d like you focus on around space_seen.

space_seen is the variable that becomes true when there’s a space before a token.

If it is met, meaning there’s a space in front of '::', it becomes tCOLON3,

if there’s not, it seems to become tCOLON2.

This is as I explained at primary in the previous section.

Identifier

Until now, since there were only symbols, it was just a character or 2 characters. This time, we’ll look at a little long things. It is the scanning pattern of identifiers.

First, the outline of yylex was as follows:

yylex(...)

{

switch (c = nextc()) {

case xxxx:

....

case xxxx:

....

default:

}

the scanning code of identifiers

}

The next code is an extract from the end of the huge switch.

This is relatively long, so I’ll show it with comments.

▼ `yylex` -- identifiers

4081 case '@': /* an instance variable or a class variable */

4082 c = nextc();

4083 newtok();

4084 tokadd('@');

4085 if (c == '@') { /* @@, meaning a class variable */

4086 tokadd('@');

4087 c = nextc();

4088 }

4089 if (ISDIGIT(c)) { /* @1 and such */

4090 if (tokidx == 1) {

4091 rb_compile_error("`@%c' is not a valid instance variable name", c);

4092 }

4093 else {

4094 rb_compile_error("`@@%c' is not a valid class variable name", c);

4095 }

4096 }

4097 if (!is_identchar(c)) { /* a strange character appears next to @ */

4098 pushback(c);

4099 return '@';

4100 }

4101 break;

4102

4103 default:

4104 if (!is_identchar(c) || ISDIGIT(c)) {

4105 rb_compile_error("Invalid char `\\%03o' in expression", c);

4106 goto retry;

4107 }

4108

4109 newtok();

4110 break;

4111 }

4112

4113 while (is_identchar(c)) { /* between characters that can be used as identifieres */

4114 tokadd(c);

4115 if (ismbchar(c)) { /* if it is the head byte of a multi-byte character */

4116 int i, len = mbclen(c)-1;

4117

4118 for (i = 0; i < len; i++) {

4119 c = nextc();

4120 tokadd(c);

4121 }

4122 }

4123 c = nextc();

4124 }

4125 if ((c == '!' || c == '?') &&

is_identchar(tok()[0]) &&

!peek('=')) { /* the end character of name! or name? */

4126 tokadd(c);

4127 }

4128 else {

4129 pushback(c);

4130 }

4131 tokfix();

(parse.y)

Finally, I’d like you focus on the condition

at the place where adding ! or ?.

This part is to interpret in the next way.

obj.m=1 # obj.m = 1 (not obj.m=)

obj.m!=1 # obj.m != 1 (not obj.m!)

((errata: this code is not relating to that condition))

This is “not” longest-match. The “longest-match” is a principle but not a constraint. Sometimes, you can refuse it.

The reserved words

After scanning the identifiers, there are about 100 lines of the code further to determine the actual symbols. In the previous code, instance variables, class variables and local variables, they are scanned all at once, but they are categorized here.

This is OK but, inside it there’s a little strange part. It is the part to filter the reserved words. Since the reserved words are not different from local variables in its character type, scanning in a bundle and categorizing later is more efficient.

Then, assume there’s str that is a char* string,

how can we determine whether it is a reserved word?

First, of course, there’s a way of comparing a lot by if statements and strcmp().

However, this is completely not smart. It is not flexible.

Its speed will also linearly increase.

Usually, only the data would be separated to a list or a hash

in order to keep the code short.

/* convert the code to data */

struct entry {char *name; int symbol;};

struct entry *table[] = {

{"if", kIF},

{"unless", kUNLESS},

{"while", kWHILE},

/* …… omission …… */

};

{

....

return lookup_symbol(table, tok());

}

Then, how ruby is doing is that, it uses a hash table.

Furthermore, it is a perfect hash.

As I said when talking about st_table,

if you knew the set of the possible keys beforehand,

sometimes you could create a hash function that never conflicts.

As for the reserved words,

“the set of the possible keys is known beforehand”,

so it is likely that we can create a perfect hash function.

But, “being able to create” and actually creating are different. Creating manually is too much cumbersome. Since the reserved words can increase or decrease, this kind of process must be automated.

Therefore, gperf comes in. gperf is one of GNU products,

it generates a perfect function from a set of values.

In order to know the usage of gperf itself in detail,

I recommend to do man gperf.

Here, I’ll only describe how to use the generated result.

In ruby the input file for gperf is keywords and the output is lex.c.

parse.y directly #include it.

Basically, doing #include C files is not good,

but performing non-essential file separation for just one function is worse.

Particularly, in ruby, there's the possibility that extern+ functions are

used by extension libraries without being noticed, thus

the function that does not want to keep its compatibility should be static.

Then, in the lex.c, a function named rb_reserved_word() is defined.

By calling it with the char* of a reserved word as key, you can look up.

The return value is NULL if not found, struct kwtable* if found

(in other words, if the argument is a reserved word).

The definition of struct kwtable is as follows:

▼ `kwtable`

1 struct kwtable {char *name; int id[2]; enum lex_state state;};

(keywords)

name is the name of the reserved word, id[0] is its symbol,

id[1] is its symbol as a modification (kIF_MOD and such).

lex_state is “the lex_state should be moved to after reading this reserved word”.

lex_state will be explained in the next chapter.

This is the place where actually looking up.

▼ `yylex()` -- identifier -- call `rb_reserved_word()`

4173 struct kwtable *kw;

4174

4175 /* See if it is a reserved word. */

4176 kw = rb_reserved_word(tok(), toklen());

4177 if (kw) {

(parse.y)

Strings

The double quote (") part of yylex() is this.

▼ `yylex` − `'"'`

3318 case '"':

3319 lex_strterm = NEW_STRTERM(str_dquote, '"', 0);

3320 return tSTRING_BEG;

(parse.y)

Surprisingly it finishes after scanning only the first character.

Then, this time, when taking a look at the rule,

tSTRING_BEG is found in the following part:

▼ rules for strings

string1 : tSTRING_BEG string_contents tSTRING_END

string_contents :

| string_contents string_content

string_content : tSTRING_CONTENT

| tSTRING_DVAR string_dvar

| tSTRING_DBEG term_push compstmt '}'

string_dvar : tGVAR

| tIVAR

| tCVAR

| backref

term_push :

These rules are the part introduced to deal with embedded expressions inside of strings.

tSTRING_CONTENT is literal part,

tSTRING_DBEG is "#{".

tSTRING_DVAR represents “# that in front of a variable”. For example,

".....#$gvar...."

this kind of syntax.

I have not explained but when the embedded expression is only a variable,

{ and } can be left out.

But this is often not recommended.

D of DVAR, DBEG seems the abbreviation of dynamic.

And, backref represents the special variables relating to regular expressions,

such as $1 $2 or $& $'.

term_push is “a rule defined for its action”.

Now, we’ll go back to yylex() here.

If it simply returns the parser,

since its context is the “interior” of a string,

it would be a problem if a variable and if and others are suddenly scanned in

the next yylex().

What plays an important role there is …

case '"':

lex_strterm = NEW_STRTERM(str_dquote, '"', 0);

return tSTRING_BEG;

… lex_strterm. Let’s go back to the beginning of yylex().

▼ the beginning of `yylex()`

3106 static int

3107 yylex()

3108 {

3109 static ID last_id = 0;

3110 register int c;

3111 int space_seen = 0;

3112 int cmd_state;

3113

3114 if (lex_strterm) {

/* scanning string */

3131 return token;

3132 }

3133 cmd_state = command_start;

3134 command_start = Qfalse;

3135 retry:

3136 switch (c = nextc()) {

(parse.y)

If lex_strterm exists, it enters the string mode without asking.

It means, conversely speaking, if there’s lex_strterm,

it is while scanning string,

and when parsing the embedded expressions inside strings,

you have to set lex_strterm to 0.

And, when the embedded expression ends, you have to set it back.

This is done in the following part:

▼ `string_content`

1916 string_content : ....

1917 | tSTRING_DBEG term_push

1918 {

1919 $<num>1 = lex_strnest;

1920 $<node>$ = lex_strterm;

1921 lex_strterm = 0;

1922 lex_state = EXPR_BEG;

1923 }

1924 compstmt '}'

1925 {

1926 lex_strnest = $<num>1;

1927 quoted_term = $2;

1928 lex_strterm = $<node>3;

1929 if (($$ = $4) && nd_type($$) == NODE_NEWLINE) {

1930 $$ = $$->nd_next;

1931 rb_gc_force_recycle((VALUE)$4);

1932 }

1933 $$ = NEW_EVSTR($$);

1934 }

(parse.y)

In the embedded action, lex_stream is saved as the value of tSTRING_DBEG

(virtually, this is a stack push),

it recovers in the ordinary action (pop).

This is a fairly smart way.

But why is it doing this tedious thing?

Can’t it be done by, after scanning normally,

calling yyparse() recursively at the point when it finds #{ ?

There’s actually a problem.

yyparse() can’t be called recursively.

This is the well known limit of yacc.

Since the yyval that is used to receive or pass a value is a global variable,

careless recursive calls can destroy the value.

With bison (yacc of GNU),

recursive calls are possible by using %pure_parser directive,

but the current ruby decided not to assume bison.

In reality, byacc (Berkely yacc) is often used in BSD-derived OS and Windows and such,

if bison is assumed, it causes a little cumbersome.

lex_strterm

As we’ve seen, when you consider lex_stream as a boolean value,

it represents whether or not the scanner is in the string mode.

But its contents also has a meaning.

First, let’s look at its type.

▼ `lex_strterm`

72 static NODE *lex_strterm;

(parse.y)

This definition shows its type is NODE*.

This is the type used for syntax tree and will be discussed in detail

in Chapter 12: Syntax tree construction.

For the time being, it is a structure which has three elements,

since it is VALUE you don’t have to free() it,

you should remember only these two points.

▼ `NEW_STRTERM()`

2865 #define NEW_STRTERM(func, term, paren) \

2866 rb_node_newnode(NODE_STRTERM, (func), (term), (paren))

(parse.y)

This is a macro to create a node to be stored in lex_stream.

First, term is the terminal character of the string.

For example, if it is a " string, it is ",

and if it is a ' string, it is '.

paren is used to store the corresponding parenthesis when it is a % string.

For example,

%Q(..........)

in this case, paren stores '('. And, term stores the closing parenthesis ')'.

If it is not a % string, paren is 0.

At last, func, this indicates the type of a string.

The available types are decided as follows:

▼ `func`

2775 #define STR_FUNC_ESCAPE 0x01 /* backslash notations such as \n are in effect */

2776 #define STR_FUNC_EXPAND 0x02 /* embedded expressions are in effect */

2777 #define STR_FUNC_REGEXP 0x04 /* it is a regular expression */

2778 #define STR_FUNC_QWORDS 0x08 /* %w(....) or %W(....) */

2779 #define STR_FUNC_INDENT 0x20 /* <<-EOS(the finishing symbol can be indented) */

2780

2781 enum string_type {

2782 str_squote = (0),

2783 str_dquote = (STR_FUNC_EXPAND),

2784 str_xquote = (STR_FUNC_ESCAPE|STR_FUNC_EXPAND),

2785 str_regexp = (STR_FUNC_REGEXP|STR_FUNC_ESCAPE|STR_FUNC_EXPAND),

2786 str_sword = (STR_FUNC_QWORDS),

2787 str_dword = (STR_FUNC_QWORDS|STR_FUNC_EXPAND),

2788 };

(parse.y)

Each meaning of enum string_type is as follows:

| Type | Meaning |

|---|---|

str_squote |

' string / %q |

str_dquote |

" string / %Q |

str_xquote |

command string (not be explained in this book) |

str_regexp |

regular expression |

str_sword |

%w |

str_dword |

%W |

String scan function

The rest is reading yylex() in the string mode,

in other words, the if at the beginning.

▼ `yylex`− string

3114 if (lex_strterm) {

3115 int token;

3116 if (nd_type(lex_strterm) == NODE_HEREDOC) {

3117 token = here_document(lex_strterm);

3118 if (token == tSTRING_END) {

3119 lex_strterm = 0;

3120 lex_state = EXPR_END;

3121 }

3122 }

3123 else {

3124 token = parse_string(lex_strterm);

3125 if (token == tSTRING_END || token == tREGEXP_END) {

3126 rb_gc_force_recycle((VALUE)lex_strterm);

3127 lex_strterm = 0;

3128 lex_state = EXPR_END;

3129 }

3130 }

3131 return token;

3132 }

(parse.y)

It is divided into the two major groups: here document and others.

But this time, we won’t read parse_string().

As I previously described, there are a lot of conditions,

it is tremendously being a spaghetti code.

If I tried to explain it,

odds are high that readers would complain that “it is as the code is written!”.

Furthermore, although it requires a lot of efforts, it is not interesting.

But, not explaining at all is also not a good thing to do,

The modified version that functions are separately defined for each target to be scanned

is contained in the attached CD-ROM (doc/parse_string.html).

I’d like readers who are interested in to try to look over it.

Here Document

In comparison to the ordinary strings, here documents are fairly interesting.

That may be because, unlike the other elements, it deal with a line at a time.

Moreover, it is terrific that the starting symbol can exist in the middle of a program.

First, I’ll show the code of yylex() to scan the starting symbol of a here document.

▼ `yylex`−`'<'`

3260 case '<':

3261 c = nextc();

3262 if (c == '<' &&

3263 lex_state != EXPR_END &&

3264 lex_state != EXPR_DOT &&

3265 lex_state != EXPR_ENDARG &&

3266 lex_state != EXPR_CLASS &&

3267 (!IS_ARG() || space_seen)) {

3268 int token = heredoc_identifier();

3269 if (token) return token;

(parse.y)

As usual, we’ll ignore the herd of lex_state.

Then, we can see that it reads only “<<” here

and the rest is scanned at heredoc_identifier().

Therefore, here is heredoc_identifier().

▼ `heredoc_identifier()`

2926 static int

2927 heredoc_identifier()

2928 {

/* ... omission ... reading the starting symbol */

2979 tokfix();

2980 len = lex_p - lex_pbeg; /*(A)*/

2981 lex_p = lex_pend; /*(B)*/

2982 lex_strterm = rb_node_newnode(NODE_HEREDOC,

2983 rb_str_new(tok(), toklen()), /* nd_lit */

2984 len, /* nd_nth */

2985 /*(C)*/ lex_lastline); /* nd_orig */

2986

2987 return term == '`' ? tXSTRING_BEG : tSTRING_BEG;

2988 }

(parse.y)

The part which reads the starting symbol (<<EOS) is not important, so it is totally left out.

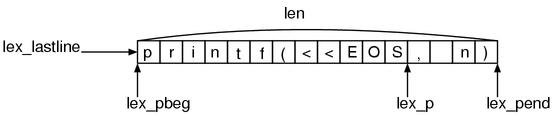

Until now, the input buffer probably has become as depicted as Figure 10.

Let’s recall that the input buffer reads a line at a time.

"printf(<<EOS,n)"What heredoc_identifier() is doing is as follows:

(A) len is the number of read bytes in the current line.

(B) and, suddenly move lex_p to the end of the line.

It means that in the read line, the part after the starting symbol is read but

not parsed. When is that rest part parsed?

For this mystery, a hint is that at ==(C)== the lex_lastline (the currently

read line) and len (the length that has already read) are saved.

Then, the dynamic call graph before and after heredoc_identifier is simply

shown below:

yyparse

yylex(case '<')

heredoc_identifier(lex_strterm = ....)

yylex(the beginning if)

here_document

And, this here_document() is doing the scan of the body of the here document.

Omitting invalid cases and adding some comments,

heredoc_identifier() is shown below.

Notice that lex_strterm remains unchanged after it was set at heredoc_identifier().

▼ `here_document()`(simplified)

here_document(NODE *here)

{

VALUE line; /* the line currently being scanned */

VALUE str = rb_str_new("", 0); /* a string to store the results */

/* ... handling invalid conditions, omitted ... */

if (embeded expressions not in effect) {

do {

line = lex_lastline; /*(A)*/

rb_str_cat(str, RSTRING(line)->ptr, RSTRING(line)->len);

lex_p = lex_pend; /*(B)*/

if (nextc() == -1) { /*(C)*/

goto error;

}

} while (the currently read line is not equal to the finishing symbol);

}

else {

/* the embeded expressions are available ... omitted */

}

heredoc_restore(lex_strterm);

lex_strterm = NEW_STRTERM(-1, 0, 0);

yylval.node = NEW_STR(str);

return tSTRING_CONTENT;

}

rb_str_cat() is the function to connect a char* at the end of a Ruby string.

It means that the currently being read line lex_lastline is connected to

str at (A). After it is connected, there’s no use of the current line.

At (B), suddenly moving lex_p to the end of line.

And ==(C)== is a problem, in this place, it looks like doing the check whether

it is finished, but actually the next “line” is read.

I’d like you to recall that nextc() automatically reads the next line when

the current line has finished to be read.

So, since the current line is forcibly finished at (B),

lex_p moves to the next line at ==(C)==.

And finally, leaving the do ~ while loop, it is heredoc_restore().

▼ `heredoc_restore()`

2990 static void

2991 heredoc_restore(here)

2992 NODE *here;

2993 {

2994 VALUE line = here->nd_orig;

2995 lex_lastline = line;

2996 lex_pbeg = RSTRING(line)->ptr;

2997 lex_pend = lex_pbeg + RSTRING(line)->len;

2998 lex_p = lex_pbeg + here->nd_nth;

2999 heredoc_end = ruby_sourceline;

3000 ruby_sourceline = nd_line(here);

3001 rb_gc_force_recycle(here->nd_lit);

3002 rb_gc_force_recycle((VALUE)here);

3003 }

(parse.y)

here->nd_orig holds the line which contains the starting symbol.

here->nd_nth holds the length already read in the line contains the starting

symbol.

It means it can continue to scan from the just after the starting symbol

as if there was nothing happened. (Figure 11)